REALIENATE YOURSELF TO BEAUTY: on William Blake

by Andrew McGlynn

Imagine for a moment you are an upper-class art lover in late eighteenth-century England. You have no idea what Tik Tok is; the photograph hasn’t even been invented yet. To you, the pinnacle of beauty, the highest form of artistic truth, likely resembles Thomas Gainsborough’s Mountain Landscape With Bridge, painted in 1784.

Or perhaps your tastes prefer portraiture, in which case you might gravitate towards Sir Joshua Reynolds’ portrait of Lady Caroline Howard, painted in 1778.

Gainsborough and Reynolds were both members of the Royal Academy of Art, and their pedigree shows in the obvious beauty on display. Both paintings have a serenity about them, a warm grace upon which you, our Anglo-art-appreciator, could meditate for hours.

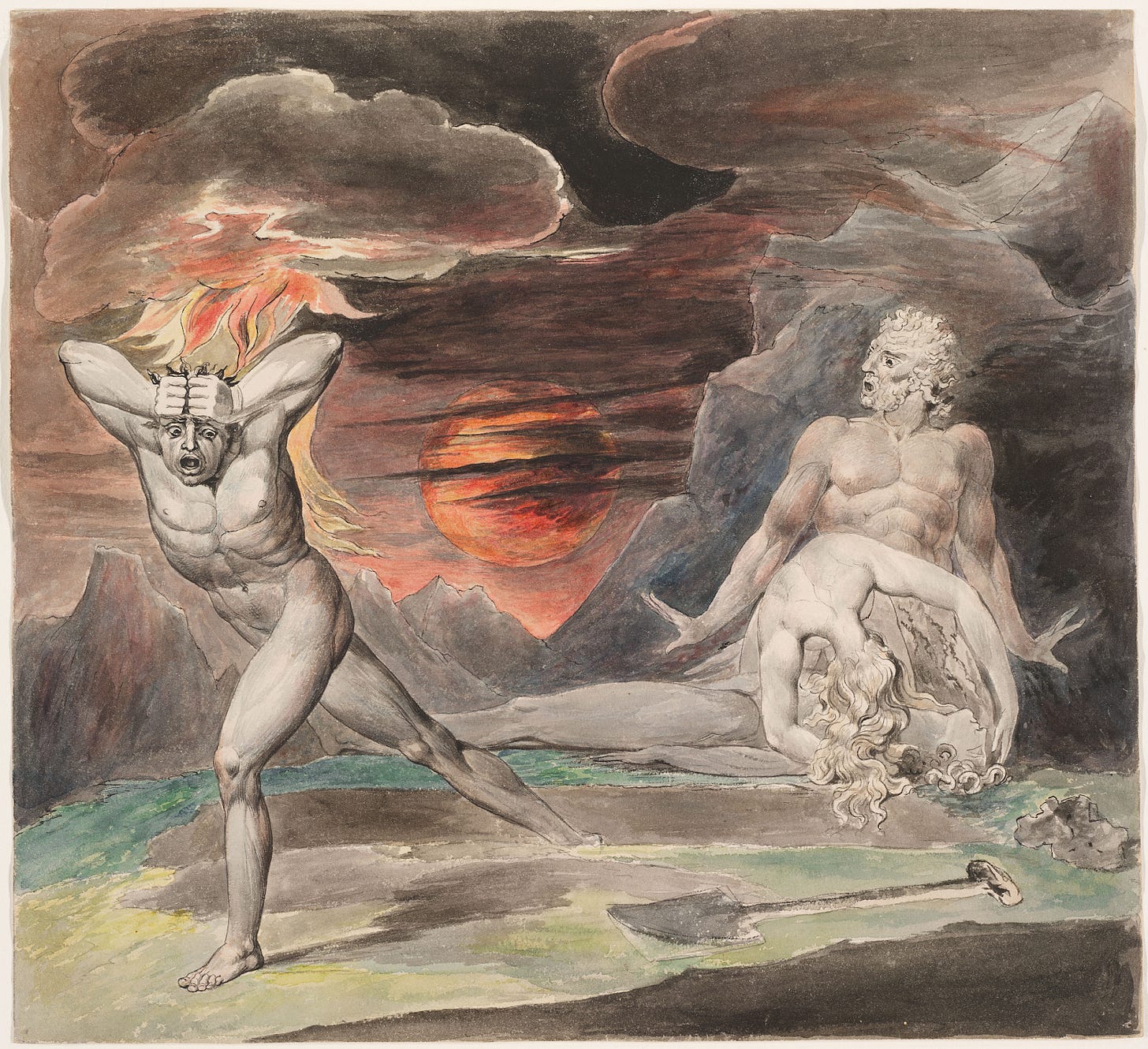

Now imagine how you would feel, your refined artistic sensibilities trained on the technical mastery and sublime peace of Gainsborough and Reynolds, upon seeing Cain Fleeing From the Wrath of God, one of painter-poet William Blake’s first completed watercolors, painted in 1799.

It’s a little shocking, isn’t it? There’s a real ugliness to Cain’s expression, as though Blake sought to encapsulate his sin within his face; it stands in stark contrast to the quiet dignity of Lady Caroline Howard. While Gainsborough’s Mountain Landscape showed you lovely, ambling hills sprouting greenery beneath a lavender sky, Blake here confronts you with ominous jagged crags and a blood-red horizon with storm clouds literally raining fire onto the scene. From the start of his painting career, William Blake sought to challenge artistic sensibilities with his uncanny visions.

Yet, the more you look at it, that very uncanniness becomes captivating. Adam’s body disappears behind Eve’s grief-stricken torso, which bends down to embrace the corpse of Abel, whose extended leg then melts into the fleeing Cain; four figures united by this one act of violence. The scenery, too, exhibits a strange unity: the gray peaks dissolve into the clouds, whose fiery discharge bleeds into the ominous sunset. You begin to wonder where in the world Blake learned to paint like that. Certainly not at the Royal Academy. The more you study Blake’s painting, the more its artistic unity is revealed, the stranger it becomes, until you are forced to reckon with the untameable otherness of Blake’s radical artistic vision, the likes of which you have never seen before.

Of course, that Blake refuses to be tamed has never stopped people from trying. If you’ve ever taken a class on British Literature, you’ve probably read “The Tyger.” “Did he who made the Lamb make thee?” Blake asks, seeking to reconcile the unfathomable beauty of the world with its equally unfathomable brutality. Through his poems and paintings, Blake sought what he termed “The Marriage of Heaven and Hell,” utilizing all of his artistic powers to identify the point at which bliss and terror become indistinguishable.

Don’t let anyone fool you: William Blake is not of this world. He is not merely a “Romantic poet” or an “English painter” or even a “visionary multimedia artist.” If you choose to accept his radical strangeness, Blake is a world unto himself, a still-uncharted wilderness brimming with strange and sinister wonders.